We are going to take a short break from our series on Asian ingredients as this time of the year, many of us turn our thoughts to our Thanksgiving meal. Some people take it in stride, while others develop a certain amount of stress trying to figure out how to get everything done on time and have it taste delicious. I have written much on this subject in prior Cooking Tips. In this Tip, I am collating all this information so it is right at your fingertips. This post contains affiliate links and I may earn a commission if you decide to purchase.

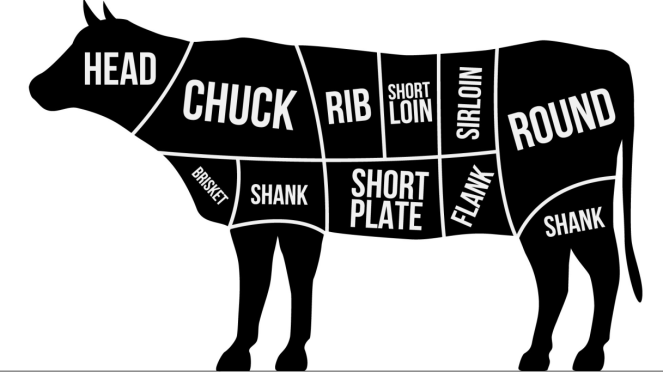

Turkey

Let’s start with the turkey. My favorite method (along with many chefs) is to do a dry brine followed by spatchcocking before putting it in the oven.

Do you always do a wet brine? Read this Tip on brining as well as the alternative of a dry brine, which is not only easier but leads to superior results. Here is also an excellent article from ThermoWorks about what brining does and why they prefer dry brining.

Rather than roasting your turkey whole, consider spatchcocking it. This means taking out the breast bone and pressing it flat before putting it in the oven. Advantages include being able to cook both the white meat and dark meat to the recommended temperatures without overcooking the white meat. Another benefit is that your turkey will cook in much less time. Here is a Tip on how to do so. It includes a link to a video by Serious Eats. Here is another ThermoWorks link, which includes an excellent video on their method.

The last thing you want to do is to have overcooked or, even worse, undercooked turkey. The above ThermoWorks discussion on spatchcocking also includes recommendations on doneness temperatures.

Potatoes

Delicious mashed potatoes are another standard on the traditional Thanksgiving table. Although they are not difficult to make, some points in this Tip can help you make them the best ever. You can also make them ahead, thus freeing your time to do other things. I wrote an article on Success & Make-Ahead Tips that will give you some options.

Pies

There will be at least one variety of pie on our holiday tables if not more than one. Here are some links to help you create the most delicious pies.

- Pie plates – Does it matter what kind of pie plate you use? See this Tip for the answer.

- Pie crust – I encourage you not to take the shortcut of a store-bought pie pastry but make your own. See these Tips for all you need to know.

- Filling – Although there are other fillings, pumpkin certainly ranks up there as one of the most popular. Did you know that the pumpkin in the Libby can is a specific type of squash? See this Tip for a discussion. Instead of grabbing for that canned pumpkin, try something different this year and make your pumpkin pie with roasted butternut squash. My husband likes to tell people he does not like winter squash, but the best pumpkin pie he has eaten is one I made with butternut squash. Here is a link to that recipe.

Spices

Certain spices make you think of the holidays. See this Tip for helpful information.

Make Ahead

The more you can do ahead of the day, the less stressful it becomes. I have given you some links above, and here is an article I wrote on that subject – Success & Make Ahead Tips. Using your freezer is a great way to get ahead of the big day. See this Tip for things you need to think about.

Leftovers

Are you in the “love them” or “hate them” category regarding leftovers? Whichever you are, you are sure to have leftovers after a large holiday meal. See this Tip for essential safety measures.

Planning

Although I put this last, planning for the big day is one of the most important things you can do to ensure a great meal and day. See this article on Thanksgiving Prep that I wrote to help you.

I sincerely hope these Tips and suggestions will help make this Thanksgiving the best ever. If there is something else that you have questions about, just let me know. If you know someone who is stressed over preparing their Thanksgiving meal, please send this Tip to them.

Happy Thanksgiving!